Fast fashion and circular economy: cherry picking and band-aid solutions

08.01.2024

Fast fashion companies seemingly stand behind circular economy, but clear objectives for increasing circular economy services or reducing production are nowhere to be seen.

“People only consume what they need. Production and consumption wastes have been fully eliminated and multifunctional, season-less and timeless fashions are the norm.“

This excerpt could be from Pro Ethical Trade Finland’s (Eetti) vision for the future.

In reality the quote is from a commitment underwritten by the ultra-fast fashion behemoth Shein. The goal of this commitment is a clothing industry that fully complies with the principles of circular economy by 2050.

However, there is a drastic disconnect between Shein’s goals and actions and the company’s current business model which is based on extremely cheap clothes and extremely fast circulation.

In 2022 Shein’s production volumes increased by 57%. At the same time its carbon footprint surged by 52%, and the company doesn’t have any ambitious goals when it comes to taking its business activities in a more sustainable direction.

Even though Shein is an extreme example of the unsustainability of clothing production, the most common circular economy actions of other big-league fashion companies aren’t sufficient to make the industry sustainable, either. Rather, they act as band-aid solutions that aim at keeping the sinking ship afloat a little while longer.

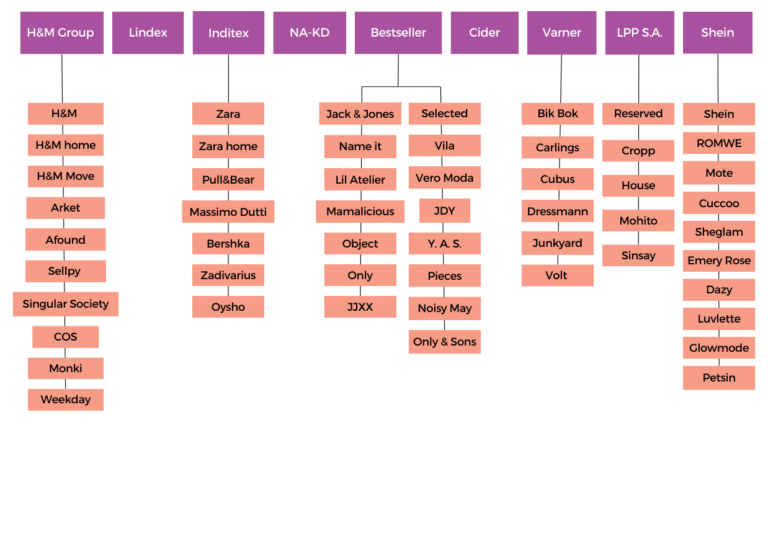

Pro Ethical Trade Finland’s report explores the current state and future prospects of circular economy actions in the clothing industry. The report focuses on nine fast fashion and ultra-fast fashion companies operating on the Finnish market: Shein, H&M Group, Lindex, NA-KD, Bestseller, Inditex, LPP S.A., Varner, and Cider.

Spoiler alert: ‘20% recycled polyester’ doesn’t quite cut it.

Table of Contents:

3. Fast fashion is fast fashion even if it’s made of recycled fibres

4. Circular economy services of companies: big talk, small goals

5. The elephant in the room: reducing production

6. No circular economy without just transition

7. Money plays the main role, circular economy plays second fiddle

8. Recommendations: the world doesn’t change if we don’t change it

1. What is circular economy?

In circular economy less clothes are being produced and bought than nowadays. They are used as long as possible by one or several users. Clothes are designed and produced so that they stand the test of time—in terms of both quality and style.

At the end of their lifecycle old clothes are recycled to be used as raw material for new ones.

The turnover of a clothing company operating in line with the principles of circular economy consists of several parts: managing, repairing, and refurbishing clothes, reselling and renting out used clothes, and selling new clothes that will serve their users for a long time.

The goal is to operate within the planetary boundaries and in a socially just manner.

There are many different definitions for the term ‘circular economy’, and, similarly to the word ‘sustainability’, it is used in various different ways. Therefore, also actions that aren’t in fact socially or ecologically sustainable can be dubbed ‘circular economy’.

2. Planetary boundaries are being exceeded left and right, but companies are only cherry picking when it comes to circular economy

According to estimations, clothing companies manufacture over 100 billion pieces of clothing in total annually, and most of the raw materials for these clothes are new natural resources. The clothing industry is in desperate need of change because the environmental impact of the industry is notable:

- The clothing industry produces over 92 million tonnes of textile waste annually.

- The clothing and textile industry is the source of up to 10% of all carbon emissions and uses 79 trillion litres of water annually.

- The production of raw materials reduces biodiversity, and the chemicals used in production pollute the environment.

The current production and consumption model leads to biodiversity loss and an ever-worsening climate crisis. Planetary limits are being exceeded at a dizzying rate.

The companies operating in the clothing industry have also realized that something needs to be done about this.

Circular economy has been a buzz word in the industry already for years, and it is thought to bring about a solution to notable environmental problems.

‘Circularity is the future of fashion’, declares, for example, Varner, which is home to brands such as Cubus, Carlings, and Bik Bok. Bestseller thinks along the same lines—their selection of brands includes Jack & Jones, Vero Moda, and Vila, among others.

Out of the companies surveyed by Pro Ethical Trade Finland, all but the Chinese–American company Cider declare that they are striving towards a future that aligns with circular economy.

There are big things in the works in the EU as well when it comes to circular economy: according to the EU Strategy for Sustainable and Circular Textiles, all textile products on the EU market will be sustainable, repairable, recyclable, and, for the most part, made of recycled fibres by 2030.

Well, this sounds good!

However, the dissonance derives from the fact that the companies’ current actions and concrete prospects for the future aren’t in line with the impressive visions.

By talking about technology, innovations, and recycled materials, companies create an image that they are doing all they can to tackle the challenges facing the industry. Yet, in reality companies are only cherry picking when it comes to circular economy.

Next, let’s dive deeper into what kinds of circular economy actions companies are taking and how credible these actions are.

3. Fast fashion is fast fashion even if it’s made of recycled fibres

In Finland, a lot of work has been done around developing new fibre innovations that aim at more environmentally friendly production methods of textile fibres. In some of these fibres, textile waste is being used as raw material.

When textile waste is used to produce raw material for new clothes, the material travels in a so-called ‘closed loop’. A closed loop means that at the end of its lifecycle a piece of clothing isn’t incinerated or it doesn’t end up in landfill; instead, it continues its life as new material.

New fibre innovations promise to revolutionize the material selection of the clothing industry and advance larger-scale utilization of old clothes.

Many of the companies included in Pro Ethical Trade Finland’s report, such as Inditex, H&M Group, Lindex, and Bestseller, have already sold small batches of clothes that have been produced using new innovations.

There is a lot of enthusiasm and buzz around these innovations, but when it comes to concreteness, there are only crickets: none of the companies surveyed by Pro Ethical Trade Finland give a numerical goal for how big of a proportion of their materials will be produced using post-consumer textile waste in coming years.

The reasons for this are obvious. Even though the required technologies for recycling textile fibres already exist, mere fibre innovations aren’t enough to turn old clothes into raw material for new ones.

The journey has only begun when it comes to turning old clothes into new ones

In the clothing industry, only less than 1% of all post-consumer textile waste ends up as raw material for new clothes. There is a lot of effort in the industry to make this percentage higher, but there are numerous bumps on the road.

One bottleneck is collection of clothes: it’s not yet systematic.

Even though a new waste legislation took effect in Finland at the beginning of 2023, obliging municipalities to collect the textile waste of their residents, collection points are still available only sparsely. The amounts of collected textile waste aren’t significant, either.

The EU textile strategy may also change the situation: with producer responsibility, companies would be responsible for collecting old clothes, not municipalities. Some clothing companies are already collecting old clothes, but at least for the time being they still end up somewhere completely different than as raw material for new clothes—in the worst case as waste in the countries of the Global South.

Even if we managed to collect clothes in increasing quantities, the next bottleneck is sorting. Clothes should be sorted based on fibres, and this is easier said than done: one piece of clothing is made up of several raw materials, and, to make it even more challenging, materials are often blends.

The bad quality of textile materials doesn’t make the situation any easier. If the raw materials are of bad quality, it is difficult to turn them into good recycled materials.

To top everything off: even though there has been a lot of hype around new fibre innovations, this hype hasn’t always materialized into money.

For example, the raw material produced by the Swedish company Renewcell hasn’t sold as expected. In turn, Infinited Fiber Company had planned to open a new factory in Kemi, but funding for this undertaking is still a question mark.

Big investments and multidisciplinary collaboration will be needed before the wheels of the ecosystem of recycling clothes start turning properly.

20% recycled polyester—quite the eco act!

So, where do the recycled materials that clothing companies are currently using come from?

Most of them come from PET plastic bottles that have been processed into recycled polyester. Some recycled cotton that derives from the clothing industry’s cutting waste is also used. Other recycled textile fibres are used minimally.

The companies surveyed by Pro Ethical Trade Finland also utilize these recycled materials.

Even though recycled materials are being promoted in a notable manner, their proportion of all materials is still small: when it comes to the surveyed companies, this only amounts to a few percent at a minimum and a good 20 percent at a maximum.

Not all companies communicate their future goals, but at a maximum the proportion of recycled raw materials is targeted to reach about 40% by 2030.

The situation of the surveyed companies aligns with the overall current state of the industry: according to the report of Textile Exchange, recycled materials made up 8,5 % of all textile materials in 2021.*

Switching to using recycled materials is essentially positive because then the use of virgin raw materials is not necessary; this includes, for example, polyester, which causes a significant burden on the climate, and cotton, which requires a lot of water and harmful chemicals.

However, when it comes to the current use of recycled raw materials, we are basically jumping out of the frying pan and into the fire: for example, the number of recyclable bottles should primarily be reduced, and the already existing bottles should circulate within the beverage industry.

Furthermore, the processing of recycled raw materials into new materials doesn’t come about without it having an impact on the environment. The production often requires lots of energy, and it can also require a great amount of water and chemicals that can be harmful to the environment.

* Revised Jan 22nd 2024: recycled materials made up 8,5 % of all textile materials in 2021.

Recycled material isn’t a miracle solution

Even if the material of a piece of clothing was made of a more ecological raw material, the environmental benefits will be quickly cancelled out if this raw material is used to manufacture a piece of clothing that doesn’t last long in use due to its quality or design.

For example, currently the production capacity of the new fibre innovations has been reserved by big fashion players such as Inditex, H&M Group, and Bestseller. The basis of the business operations of these companies is to sell large amounts of affordable clothes at a rapid pace.

Therefore, the fast fashion problem won’t be solved by these companies switching to recycled materials if those materials will be used to manufacture party tops costing 10 euros.

4. Circular economy services of companies: big talk, small goals

Many of the companies included in Pro Ethical Trade Finland’s report have started to offer second-hand products and repair services. Lots of companies are also raving about the possibilities of clothing rentals. Exactly how significant are circular economy services with regard to the companies’ business operations?

Second-hand is only good if it replaces new clothes

Out of the companies surveyed by Pro Ethical Trade FInland, only one, the Swedish NA-KD, publishes a precise percentage for how much of the 2022 revenue came from circular economy services: 0.27%. This equals 37,000 sold second-hand pieces of clothing and represents about half a million euros in NA-KD’s revenue.

In turn, Lindex announces having sold over one million pieces of used clothing, but according to the company’s information, the amount is not yet at a level where it would amount to a precise percentage.

This tells a lot about scale: so many new clothes are being sold that a million pieces of clothing don’t make much of a difference when talking about Lindex’s revenue of over 600 million euros.

Judging by the data published by the companies, it seems that their second-hand services are still a very small business.

However, all in all reselling of clothes is on the rise: at the moment, second-hand sales cover about 3.5% of the global clothing market, and they are expected to grow 11 times faster than the sales of new clothes.

At least up until now, instead of clothing brands, the players responsible for the growth of the second-hand market have been online stores, brick and mortar stores, and platform services that have based their business operations on selling used clothes from the very beginning.

It is probable that going forward the surveyed companies will want to have their piece of the pie as well when it comes to this market. For example, H&M Group is the main owner of the Swedish second-hand online store Sellpy.

The used clothes sold by companies are a positive step, but when we think about the environment, the positive effect isn’t that straightforward. If the second-hand sales are an addition to selling new clothes and they don’t as such replace selling new clothes, the negative impact these companies have on the environment isn’t getting any smaller.

Buying used clothes can also maintain the fast circulation of clothes and enable buying new clothes without remorse because ‘the clothes can always be recycled’.

In reality, only a tiny proportion of all these used clothes is sold because there are way too many clothes in circulation.

Clothing rentals mustn’t repeat the fast fashion pattern

The companies included in the report have not invested notably in clothing rentals—at least not yet. For example, H&M has a clothing rental service, but it is a very small-scale operation.

There hasn’t been a shift to an era of rental services in the clothing sector in a broader sense either even though it has been a hot topic already for years. There are many reasons for this, one of them notably being that renting requires a completely new model both for consuming and business operations.

Renting has an opportunity to be an ecological service model for circular economy, but, just like second-hand services, it isn’t automatically an environmentally friendly option.

For example, a big American rental platform Rent the Runway offers its members ten pieces of clothing every month, delivered to their door. This type of renting keeps alive the fast fashion sentiment that we need something new to wear all the time.

Then again, renting can also work well locally and in a more environmentally friendly manner. A Finnish clothing rental chain Vaatepuu serves as an example of this: 88 % of members who filled out the member survey told that their clothing consumption has decreased since they became members of the rental service.

The environmental impact of renting is also affected by, for example, the quality and longevity of the products offered by the service and how long they will stay in circulation.

Turning quality into business

Many of the surveyed companies offer small-scale services, instructions, and products for clothing repair and maintenance.

On the one hand these help the customer extend the life span of their clothes, and on the other hand they help paint a picture of the brand as a supplier of high-quality clothes. These actions will, however, remain on the surface level if the longevity of the clothes themselves isn’t addressed.

The upcoming EU Ecodesign Directive has probably guided companies’ actions already before coming into effect. For example, many companies state that they invest in the design and longevity of their products so that they align with the principles of circular economy. Design does indeed have a central role in how long the clothes will maintain their quality in use and how their recycling will be facilitated.

There hasn’t yet been anything to indicate that longevity would be a more prominent factor in the design of clothes or in the pace at which new products pop up on the market. If the design is linked to a transient trend, it won’t remain current even if the fabric is of high quality.

If companies wanted to, they could harness their incredibly effective skills to brand and market the idea that a long-lasting product is the most desirable option.

Yet, the business model of most clothing companies hasn’t been built on products that are long-lasting and that can be repaired and maintained; rather, it has been built on the idea of fast circulation. For this reason, it’s no wonder that fast fashion and ultra-fast fashion companies aren’t exactly racing to offer long-lasting and maintainable products.

Clear goals for the growth of circular economy services are missing

According to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, the circular economy business has the potential to grow to cover 23% of the global clothing market by 2030.

Changing the business doesn’t happen in a flash, especially when we’re talking about companies whose business model is based on producing and selling new products.

However, this is a change that needs to happen.

Most of the companies included in Pro Ethical Trade Finland’s report are testing circular economy services at least on a small scale. Only in the case of Cider these services are nowhere to be seen.

Out of the surveyed companies, only the Swedish NA-KD had a published, numerical goal for the circular economy services of the future: 20% of the company’s revenue is supposed to come from circular economy business models by 2030.

Similar specific goals are rare but not unheard of.

For example, the French group LVMH that specializes in luxury goods and has Louis Vuitton among others in its brand selection, has set a goal that by 2030 25% of profits will come from circular economy services instead of new products.

In turn, the British department store chain Selfridges is aiming to get 45% of the business of its four stores and online store from circular economy products and services by 2030.

It isn’t to say that other companies don’t set other numerical goals that are generally related to their business operations for the long term.

H&M, for example, has an ambitious goal of doubling its revenue by 2030 (from the 2021 level) and simultaneously cutting its carbon footprint in half.

On its website, the company specifies that their intention isn’t to double their production or sell double the amount of products; rather, the circular economy business has a central role in reaching this goal.

One can only guess how central this role is. Shein, H&M Group, Lindex, Bestseller, Inditex, LPP S.A., Varner, and Cider don’t publish numerical goals for how much of their business will be made up of circular economy services.

The companies’ measurable goals act as good indicators of what each company invests in and what it finds particularly important. Correspondingly, if there aren’t any measurable goals, the company can’t be held accountable for not reaching them.

5. The elephant in the room: reducing production

When talking about circular economy and sustainable clothing industry, one theme that is fundamentally related to these topics is almost always absent.

Production should be reduced, period.

It isn’t an easy feat, but it’s imperative. More and more clothes are being sold, and increasing production volumes have largely cancelled out the positive developments of the clothing industry.

For example, according to a recent report, companies that make up 62% of the textile market in Great Britain had succeeded in reducing the carbon footprint of their textiles by 12% over three years.

Yet, in this same time period the production of the companies had increased by 13%. This is to say that, all in all, the total carbon footprint reduced by only an insignificant 2%.

Clothing companies: what is this reduction you’re talking about?!

None of the companies surveyed by Pro Ethical Trade Finland present goals for reducing production in the future.

However, one company—NA-KD once again—has already reduced it. The company’s production volumes of 2022 were 38% smaller than in 2020.

Then again, the reason for this might be the challenges of recent years for businesses, not so much the worry over the state of the environment. You see, NA-KD states that from now on they can increase production volumes by 5% annually because they think that sufficient emission reductions have already been reached.

Reductions are hard to come by in the industry in general: out of 250 brands included in the Fashion Transparency Index 2023 study, only two, Armani and United Colours of Benetton, have made a commitment to reduce their production. Still, these companies don’t communicate concrete percentages with regard to their reduction goals, either.

There seems to be no end in sight when it comes to growth: it has been estimated that the global clothing industry may grow by up to 63% by 2030.

The first step towards reducing production is elimination of overproduction: companies should only produce to meet the actual demand, i.e., what is actually sold. Indeed, according to one estimation, up to 30% of manufactured clothes will never be sold.

Yet, the mere reduction of overproduction is only the first step: the production volumes of sold products also need to be reduced, especially when it comes to big-league clothing brands.

Constant growth isn’t possible in circular economy

Many clothing companies, such as H&M and Bestseller, are aiming at decoupling growth from the use of limited natural resources. In other words, the companies believe that they can grow their business without increasing the use of natural resources.

However, there’s no proof of absolute decoupling of natural resources on a global scale. This is to say, there’s no evidence to support the notion that growth can continue while the consumption of natural resources decreases at the same time.

Circular economy actions don’t automatically reduce production if a company doesn’t specifically aim at reducing production. Moving to a closed loop can even increase total production. This is described as the rebound phenomenon: when the environmental impact of an individual product decreases, total production can be increased.

The same phenomenon can be seen in energy efficiency. When energy efficiency improves, the total consumption of energy doesn’t necessarily decrease; on the contrary, it can increase.

Observing the situation solely through the lens of circular economy isn’t enough: we need a much wider perspective where we aren’t afraid to question the goal of growth and the constant need for something new.

6. No circular economy without just transition

We can’t talk about circular economy—or any other environmental questions related to the clothing industry for that matter—without considering the negative impact the clothing industry has on human rights.

The current circular economy actions don’t solve the social problems that run rampant in the clothing industry, one of these problems being that most of the people working in the industry don’t earn a living wage.

On the contrary: if circular economy is executed badly, it can make the situation even worse.

It is often envisioned that with circular economy production can move back closer to Europe, even to Finland. This has a positive impact on employment at the local level but a negative one at the global level.

Most of the clothing industry jobs are currently in the low-income countries of the Global South.

If the production possibly moves away from the current production countries and the production volumes decrease, this would mean smaller order volumes for the factories. In the current production model, which is based on cheap prices, this would lead to fewer jobs for sewers.

Furthermore, once we shift more and more from virgin raw materials to recycled ones, less and less farmers will be needed in cotton fields and processing of traditional materials.

When shifting to circular economy, clothing companies should consider the current employees of the clothing industry. They can do this, for example, by including the production’s environmental and human rights impact in the prices and enabling retraining so that the employees can take on new work responsibilities, which will be created in, for example, sorting, recycling, maintaining, and repairing of clothes.

If social justice isn’t built into circular economy, it will continue to maintain the colonial power structures that the modern clothing industry has been built on.

7. Money plays the main role, circular economy plays second fiddle

The scale of the change that is needed in the clothing industry is unprecedented. It requires largely multidisciplinary collaboration, significant investments, ambitious legislation, and revised business structures—and let’s not forget about reduction of production.

Yet, it’s not surprising that companies come up with small band-aid solutions instead of implementing fundamental changes.

At the moment, the best profits are obtained by using unecological materials to manufacture large volumes of poor-quality clothes that sewers put together with salaries that aren’t sufficient for them to support themselves.

This unsustainable business model is the basis of most clothing companies, ranging from fast fashion companies and luxury brands all the way to the clothing production of hypermarkets.

Of course, we can’t generalize that all companies in the clothing industry work like this. There are numerous small and medium-sized companies in the industry that are swimming against the current.

Perhaps in the future, some completely different actors will take centre stage on the clothing market instead of the current fast fashion giants. Agile new-wave companies don’t carry any burden from ‘the old world’ where clothes were once seen as something disposable.

8. Recommendations: the world doesn’t change if we don’t change it

There isn’t any easy or quick solution to bring about the change that is needed in the clothing industry.

Nevertheless, we can’t stick solely to small and easy changes. Instead, we need to envision what a better version of our world could look like in the future.

Pro Ethical Trade Finland drives change in many different ways: we push companies to advance corporate responsibility step by step, and we encourage decision makers to proceed towards more ambitious regulations one clause at a time.

Additionally, we make longer-term goals part of the social debate because band-aids only act as quick fixes.

Recommendations for clothing companies

- Circular economy 2.0: Companies must make a time-bound plan for how circular economy services will replace the revenue obtained from selling new clothes in a way where unsustainable production volumes start to decrease.

- Just transition: Companies must map out the impact of circular economy and the green transition on human rights in the entire value chain.

- Sustainability communication: Companies must communicate about matters related to sustainability in a precise and transparent manner.

Recommendations for decision makers

- Corporate sustainability due diligence directive: Finland and the EU must work towards finalizing the directive before the European Parliament election of spring 2024.

- ‘Green claims’ directive: Finland and the EU must work towards finalizing the ‘green claims’ directive before the European Parliament election of spring 2024.

- The EU Strategy for Sustainable and Circular Textiles: Finland and the EU must advance the actions of the strategy in a way where the focal point is prevention of waste generation, reduction of production, and lengthening of the life cycle of clothes. They should also make sure that the principles of just transition are followed when implementing this strategy.

Recommendations for individuals

- Be critical: Take the circular economy claims of companies with a grain of salt and do your own research.

- Consider each purchase carefully: Skip seasonal trends and maintain the clothes you already own instead of buying new ones.

- Make a difference: Instead of just focusing on making better individual consumer choices, become an active citizen and push for ambitious legislation.

This is how Pro Ethical Trade Finland’s survey was carried out

Pro Ethical Trade Finland’s circular economy survey of the clothing industry focused on finding out whether the circular economy actions of fast fashion companies operating in the industry are sufficient to offer a solution to the significant climate and environmental problems of the clothing industry.

Pro Ethical Trade Finland surveyed nine fast fashion and ultra-fast fashion companies operating on the Finnish market: H&M Group, Lindex, NA-KD, Bestseller, Inditex, LPP S.A., Varner, Shein, and Cider.

Pro Ethical Trade Finland surveyed the following:

- Which percentage of the materials used by the companies is recycled and which percentage out of these comes from post-consumer waste? What are the companies’ numerical and time-bound goals for increasing the percentage of recycled materials in the future?

- Which percentage of the companies’ business comes from circular economy services, such as repairing, renting, and second-hand services? What are the companies’ numerical and time-bound goals for increasing the proportion of circular economy services in the future?

- Have the companies published goals for reducing production?

A table including the questions and the companies’ data can be found in a PDF format here.

The data related to the surveyed companies that has been used in this report is from 2022, and it is from sources that are available to the public, such as company websites and responsibility reports.

Furthermore, other studies and reports have been utilized in the survey, and they have been referenced as hyperlinks embedded in the report.

Pro Ethical Trade Finland contacted all the companies included in the survey by email. H&M Group, Lindex, NA-KD, and Bestseller replied by email, and Pro Ethical Trade Finland engaged in dialogue with these companies. By contrast, Inditex, LPP S.A., Varner, Shein, and Cider didn’t reply at all.

The survey has been carried out with the support of the Ministry for Foreign Affairs in Finland and crowdfunding. Thank you to everyone who donated!